The first researcher to set out the series of practice swords used in the British Army was Brian Robson, in his seminal Swords of the British Army. What I aim to do here is build on that skeleton with some further information and statistics.

Robson notes that there were essentially two types of practice swords; those intended for compliant cavalry drill and those intended for competitive fencing (both on foot and mounted). These are two distinct groups and are not the same swords.

The former were generally blunted cavalry swords of the pattern which had last been in service, hence making economical use of now obsolete weapons. They were used principally to 'go through the motions' of the practice drill, in a non-competitive manner. These blunted cavalry swords are encountered relatively often in the antique community and are instantly recognisable from standard cavalry swords by their deliberately rounded tips.

The second group were specially made fencing weapons, with slightly lighter and more flexible blades, intended to be used competitively with protective clothing and masks or helmets. They were recorded in the official documents as 'practice' and 'gymnasia' patterns and in modern historical fencing this has led to them commonly being referred to as 'gymnasium sabres'. This is the group of swords we shall be looking at here.

Singlesticks & Foils

The first official regulation fencing sword to be adopted by the British Army could be argued to be the basket-hilted singlestick, which had been the practice stand-in for the broadsword and sabre since swordsmanship manuals were adopted as regulation in the Napoleonic era (in 1796) and unofficially for centuries before the swordsmanship manuals were introduced. The humble singlestick remained in use in the British military and even in some civilian circles (e.g. Boy Scouts), basically unchanged in design and construction, until after WW2.

The next regulation fencing sword to be introduced to the British Army was the foil. This also had been around for a long time unofficially and of course was the practice tool for smallsword fencing in the 18th century. Foil fencing had long been recognised as a grounding for officers in the British Army, both for equipping them for the gentlemanly requirements of honour (the duel), but also as a technical basis for swordsmanship with military swords such as the spadroon, broadsword and sabre. Anthony Gordon's treatise of 1805 introduced a system of use for the 1796 regulation spadroon which is clearly related to the use of the smallsword.

By the middle of the 19th century foil fencing was still seen as a good grounding for all swordsmanship (and even the use of the bayonet and pike) and together with moves in the British military and navy to introduce more gymnastic rigor to the training of soldiers, a regulation British Army foil was ordered, to equip military gymnasia.

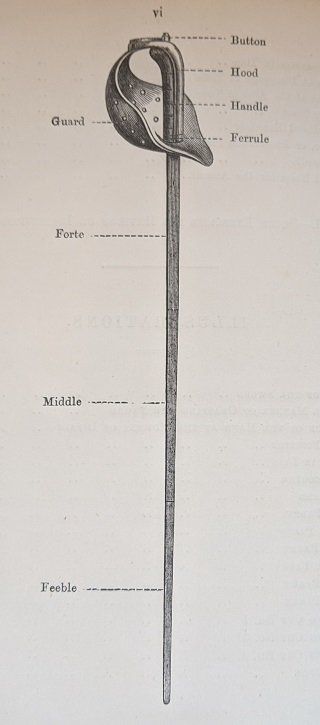

Pictured above is a late-Victorian example of a British Army foil, with the Enfield Arms Factory approval stamp clearly visible on the forte of the blade. It is typical of the kinds of foils being used by both civilian fencing clubs and the Army gymnasia at this time, having a figure 8 guard reinforced with a buff leather insert and with a long squared section grip. Its statistics are recorded in the table below.

British Army 'Gymnasium Sabres', Or Practice Swords

As detailed in my previous article, after the Crimean War the British Army and Navy went through a long and gradual process of modernisation and reform. This was a major factor behind the adoption of official regulation practice swords, to equip the new Army gymnasia, and the first regulation 'gymnasium sabre' was approved in 1864.

While flexible fencing sabres and broadswords had existed before, this was the first regulation pattern for the whole British Army, specifically designed for competitive fencing.

It roughly corresponded in size and weight to the infantry officer's service sword, though these were used by all branches of the service including cavalry. Statistics vary between individual examples, but this representative example's stats are given in the comparison table below (and you can see comparative examples in my previous article).

Sword, Practice, Gymnasia, Pattern 1864:

This 1864 Pattern remained regulation until 1895, when a new pattern was introduced, to correspond with the new service swords for infantry officers (designed under the principle leadership of Colonel G M Fox) and the corresponding new Infantry Sword Exercise of 1895. This was based on the teachings of Florentine master Ferdinand Masiello, as detailed in another of my previous articles.

From the 1880s the newer Radaelli-inspired sabre fencing styles (such as Masiello's) coming out of Italy were influential all over Europe and this accordingly led to the introduction of styles of practice fencing sword from those schools.

When the new Masiello sabre system was introduced officially in Britain in 1895, so too was the Masiello style of fencing sabre. The following few patterns of British Army fencing sabre owed much of their design to those in use by the fencing masters Masiello, Sestini and Pecoraro.

However, it appears that most British 1895 pattern fencing sabres are heavier than Masiello's versions were. Secondly, the blade design on the British swords follows Colonel Fox's 1892 Pattern blade, having a half-length central fuller, such that the bottom half of the blade from the hilt is not edged and not simulating an edged sword. Therefore it seems that rather than being a straight copy of Italian models, the 1895 Pattern married a fundamentally Italian hilt with a blade of Fox's own design.

Sword, Practice, Gymnasia, Pattern 1895:

This example of the 1895 Pattern gymnasium sabre features a flexible practice blade modeled on the 1892 Pattern infantry officer's sword blade (designed principally by Colonel Fox), with a 'dumbbell' cross-section in the forte. The blade carries the proof stamp of Wilkinson and it is dated to December 1896.

The hilt's design, being modeled on certain Italian models, is not really similar to the real 1895 or 1897 Pattern infantry officer's sword. This hilt has more complete hand protection and a narrower grip. As well as the sides of the guard which project very far down, to give as much lateral protection as possible, the part of the guard that joins the pommel has folded out 'flaps' which keep opposing blows further away from striking the little finger (a vulnerability of sabre hilts). This feature is also seen very clearly on fencing sabres in Italy, such as Masiello's.

The backstrap is again modeled on contemporary Italian fencing sabres, featuring a broadly chequered surface and flattened area for the thumb to sit. The hilt is secured to the tang by a shaped nut, allowing easy replacement of the blade.

The guard is reinforced by a thick plate, which both acts as a washer, to prevent the blade from 'eating' through the guard plate, as well as increasing the feeling of mass in the blade. This makes the sword feel more like the stiff-bladed real weapon. The size of this washer, or plate, varies between examples of the 1895 and 1899 Patterns and can lead to quite differently handling weapons.

There is variation between examples, in terms of weight, blade type and whether the guard has perforations or not.

The stats for this example are given in the table below and it should be noted that, despite some statements to the contrary in both period and modern texts, this was not a lighter practice weapon than the one that had gone before. It was approximately the same weight as the infantry officer's service sword still, which had stayed in the same weight range from 1845, though the 1892, 1895 and 1897 patterns to the present day.

Apart from the outward appearance, what had changed was that this new weapon had a point of balance closer to the hand, as will be readily seen in the table below. This can lead to the weapon feeling lighter in the hand, even if it is actually not literally lighter.

Sword, Practice, Gymnasia, Pattern 1899:

Robson states that the only difference between the 1895 Pattern and the 1899 Pattern was the perforated guard as seen here. However, as he points out, the 1899 Pattern also had a narrower blade.

The motivation for a new pattern only 4 years after the introduction of the 1895 Pattern is rather obscure, but the intention seems likely to have been to make the practice weapon lighter. That making the weapon lighter was the intention is supported by the guard perforations and the narrower blade. Though it should be noted again that examples vary in weight and proportions, and I have not measured enough examples to confirm that they are universally lighter than the 1895 Pattern.

The 1895 Pattern was approximately the weight of the real service sword (for infantry officers), whereas the 1899 pattern (at least this example) is notably lighter. Comparative stats can be found on the table below and the contrast is stark.

The difference between these two swords goes further, in that the 1899 example used here has an 'edged' blade (or edge beveled, as it is not sharpened) from the ricasso shoulder to the tip. In contrast the 1895 Pattern has a blade with no edge bevel and a dumbbell cross-section, like the actual service sword.

The question as to why these changes were made has to be pondered, but at the current time no certain answer is possible. It seems likely that the authorities wanted a less potent fencing weapon, less capable of causing injury, or perhaps there was a drive to introduce the 1899 Pattern simply because it was closer to Masiello's original fencing swords. Indeed, with no markings on this example, it is possible that this is not officially the 1899 Pattern and that this is simply based directly on Masiello's 2nd model of fencing sabre (which presumably were being sold in Great Britain outside the official military regulations). More examples need to be studied and more research is required.

These images below hopefully illustrate the contrast between the two blade designs, with the narrower 'edged' type being more typical of Italian sabres:

It remains unclear whether these two distinct blade types (which we could perhaps term the 'British' and 'Italian' types) were contemporary options (something which may be hinted at with the 1907 Pattern examples to follow), or whether the switch from one to the other happened in 1899.

The overall form of the hilt did not really change from the 1895 to 1899 Patterns and it stayed close to Masiello's originals (if anything, with the addition of the perforations in 1899, it got closer to Masiello's sabre). As always with swords of this era, individual examples vary in exact shape, weight and proportion, making it harder to define exactly what the Pattern changes were intended to be.

The overall form of the hilt did not really change from the 1895 to 1899 Patterns and it stayed close to Masiello's originals (if anything, with the addition of the perforations in 1899, it got closer to Masiello's sabre). As always with swords of this era, individual examples vary in exact shape, weight and proportion, making it harder to define exactly what the Pattern changes were intended to be.

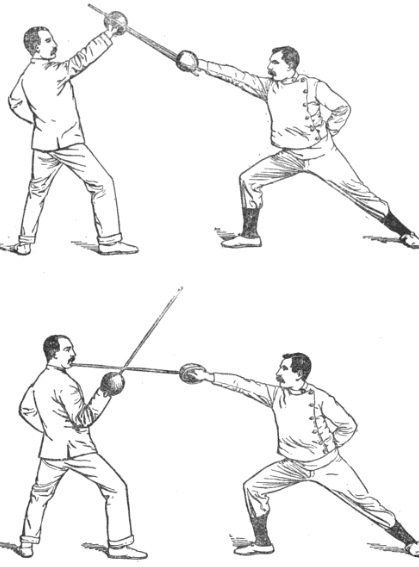

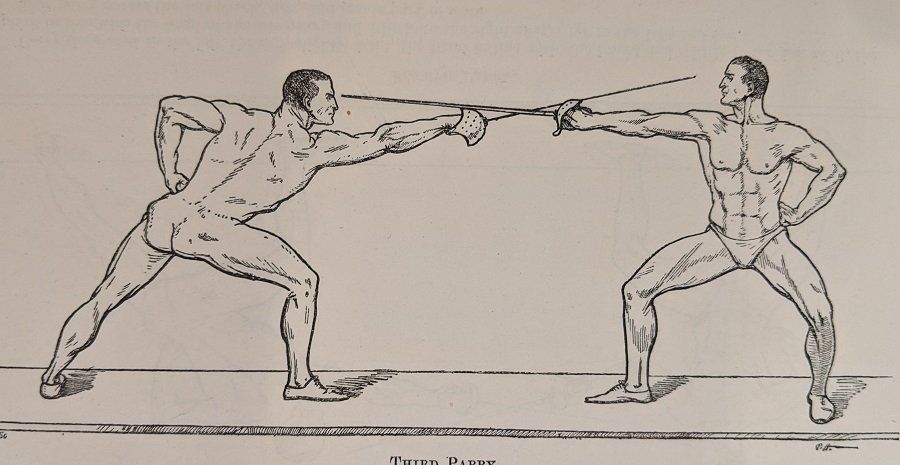

One final curiosity is that while on paper it seems that the 1899 Pattern introduced the guard perforations, when we look at the 1895 Infantry Sword Exercise, we see guards with perforations already in 1895, though this may simply be explained by these illustrations showing Masiello's 2nd model fencing sabre, rather than the British 1895 Pattern per se.

Robson writes about a 1904 Pattern gymnasium sabre, but much mystery surrounds it. I have discussed this model of sword with other collectors over the course of a few years and we have not managed to nail it down.

Robson describes it as being like the 1899 Pattern, but with an un-perforated guard and having a stiffer blade. That sounds to me exactly like the earlier 1895 Pattern as exampled here (which is clearly dated on the blade to 1896). I have never seen an antique example of a gymnasium sabre that could qualify as this supposed 1904 Pattern.

Robson describes it as being like the 1899 Pattern, but with an un-perforated guard and having a stiffer blade. That sounds to me exactly like the earlier 1895 Pattern as exampled here (which is clearly dated on the blade to 1896). I have never seen an antique example of a gymnasium sabre that could qualify as this supposed 1904 Pattern.

Robert Wilkinson-Latham, formerly of the Wilkinson Sword Company, stated on Swordforum that both Wilkinson and Mole were contracted to make the gymnasium sword 1904 Pattern and that these were completed in 1905. However, we remain at a loss to identify any surviving examples and Mr. Wilkinson-Latham could not locate any drawings of it from his records.

We are also left with no explanation for why this pattern was deemed necessary. Perhaps it was simply a re-issue of the 1895 Pattern to replenish gymnasia supplies.

Sword, Practice, Gymnasia, Pattern 1907:

The 1907 Pattern gymnasium sabre, according to Robson, was released in two versions, the Mark 1 in 1907 and the Mark II in 1909. I cannot tell (due to lack of details or markings) whether what I have are Mark I or II.

They are instantly recognisable as 1907 Patterns by their cast aluminium grips, but otherwise in general form are somewhat similar to the 1895 and 1899 Patterns that went before.

There are some bewildering questions around this pattern though - why was it necessary to release a new fencing sabre in 1907 and why was it then necessary to update it in 1909? No clues seem to survive to answer why the previous 1895, 1899 and 1904 Patterns were not sufficient and it is very curious that this new 1907 Pattern saw the overall weight increase again, to be in line with what the 1895 and 1864 patterns had been. Other than the new grip construction, it is difficult to ascertain why this model was required and what it functionally offered that was new.

Perhaps even more curious, as seen in the two examples above and below, this 1907 pattern could be furnished with either a perforated or un-perforated guard, or indeed the 'edged' blade, or the dumbbell blade. For a regulation pattern, it seems to have had a wide degree of variation possible. This is also true of the statistics, which are included in the comparative table below.

Sword, Practice, Gymnasia, Pattern 1911

This was the final model of 'gymnasium' sabre to be introduced, before the abandonment of military style practice sabres and the adoption of Olympic type sporting weapons.

It is clear that the 1911 Pattern owed its design to the form of the new 1908 Pattern cavalry sword, having a close replica of the cavalry sword grip (as designed by Colonel Fox), but in aluminium. The guard and blade also closely match the cavalry sword design, although made lighter. The blade on the 1911 Pattern practice sword is highly flexible, probably too much so, and the overall weight is notably lower than the real weapon. Though it is still substantial for a fencing sabre and it is heavier than any of the other 'gymnasium' sabres featured here (see the table below).

Like the previous models, the pommel is furnished with a nut, so that the blade can be replaced. It should be noted that the example used here has, for reasons unknown, been sharpened at the tip, though it seems to have lost barely any of its length.

This particular example was made by Wilkinson in 1915:

Robson implies that this 1911 Pattern replaced the earlier patterns, but given how specialised this design is on the new cavalry sword, it seems more likely to me that this only replaced the earlier patterns in cavalry regiments. I cannot see infantry officers using this, when the far more appropriate earlier patterns were available. Additionally, this 1911 Pattern is rather rare.

Comparative Table of Statistics for British Practice or 'Gymnasium' Sabres:

Regulation foil: Blade 85.5cm, Mass 445g, Point of Balance 4cm from guard surface

1864 Pattern: Blade 82.5cm, Mass 790g, Point of Balance 12.5cm from guard surface

1895 Pattern: Blade 86.3cm, Mass 830g, Point of Balance 6cm from guard surface

1899 Pattern: Blade 85.3cm, Mass 615g, Point of Balance 5.5cm from guard surface

1907 Pattern ('edged Italian' blade): Blade 89.5cm, Mass 770g, Point of Balance 6cm from guard surface

1907 Pattern ('dumbbell British' blade): Blade 85.7cm, Mass 750g, Point of Balance 4.5cm from guard surface

1911 Pattern: Blade 86.8cm, Mass 875g, Point of Balance 2.5cm from guard surface

British 'gymnasium' sabres/swords were heavily influenced by Italian fencing sabre models from 1895-1907. The final 1911 Pattern was closely modeled on the actual 1908 cavalry sword and was a departure from previous Patterns.

Some people (Robson included) have compared these gymnasia swords to modern fencing sabres, as used in the Olympics. Indeed, it could be argued that these were the origin of those, but anybody familiar with both types of training weapon will quickly observe the difference. The lightest sabre here, the 1899 Pattern, is 615g, while the heaviest is 875g. Olympic style fencing sabres usually weigh less than 400g and a vintage Wilkinson example I have weighs in at 380g. The widespread switch to these super light fencing sabres seems to have happened after WW1, as sabre fencing moved ever away from military science and towards Olympic achievement.

While attempts have so far been made to precisely outline these various patterns, we meet variations and exceptions at every turn.

We read of perforated and un-perforated guards being specific to certain patterns, but then seem to find them on patterns that they were not supposed to be present on.

We read of changes to blade designs and proportions, but then find that the antiques exhibit different blade types and that they come in a variety of weights and sizes.

It seems that at best we can only talk in general terms. Perhaps the regulation Pattern specifications themselves were fixed, but it seems that the actual swords being ordered and manufactured certainly were not fixed.

Some people (Robson included) have compared these gymnasia swords to modern fencing sabres, as used in the Olympics. Indeed, it could be argued that these were the origin of those, but anybody familiar with both types of training weapon will quickly observe the difference. The lightest sabre here, the 1899 Pattern, is 615g, while the heaviest is 875g. Olympic style fencing sabres usually weigh less than 400g and a vintage Wilkinson example I have weighs in at 380g. The widespread switch to these super light fencing sabres seems to have happened after WW1, as sabre fencing moved ever away from military science and towards Olympic achievement.

In the British Military it seems that practice and service swords for infantry officers remained about the same weight as they had been for the previous several decades. From the 1864 Pattern to the 1907 Pattern, the weights generally remained in the 750g-850g range most of the time (corresponding closely to the real service swords). What did change with the practice swords was a general movement of the point of balance back towards the hilt (a feature highlighted as desirable in Masiello's manual).

During this period there were also non-regulation fencing sabres of different designs being produced, like those described and shown in Captain Alfred Hutton's manuals from 1889 onwards, but those are outside the scope of this article. It is possible that in the British civilian fencing clubs, influenced by Continental trends, lighter and lighter fencing sabres were coming into use, led by Olympic regulations after 1904.

A personal goal of mine now is to establish whether the Fox 1892 type 'dumbbell' blade was regulation standard for these fencing swords and whether the alternative 'edged' Italian style blades were a regulation option, or whether they were private preference. I find it very strange that both blade types are in evidence across this period when so much attention was being paid every few years to new regulation patterns. Is it possible that different branches of the service used the different blades? Did artillery or cavalry practice with a different blade type to infantry? This might make sense, but history does not always make sense.

Hopefully this record of examples and experience will prove useful to readers in identifying antique examples and with time and work perhaps it will be possible to answer some more of the unanswered questions raised here.

Hopefully this record of examples and experience will prove useful to readers in identifying antique examples and with time and work perhaps it will be possible to answer some more of the unanswered questions raised here.