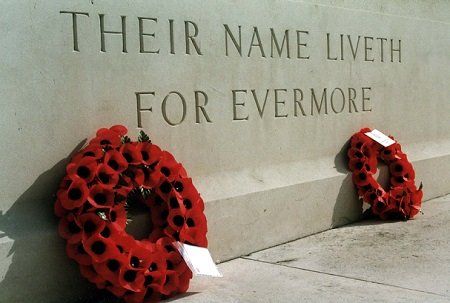

It seems fitting on this, Armistice Day 11th November 2018, the 100th anniversary of the end of WW1, to honour a fallen soldier.

This sword recently came into my possession and even without the provenance would have attracted my attention, as fitting exactly into the kind of swords I specialise in: non-regulation, or rather special order, officers’ fighting swords. It was made in 1897 by Wilkinson for an officer of the 4th Gurkha Rifles who served in war and peace for over two decades, ultimately giving his life.

The sword itself is non-regulation in 3 basic features:

1) The blade is not the regulation 1892 pattern thrusting blade designed by Colonel Fox, nor the earlier type of fullered cut and thrust sabre blade designed by Henry Wilkinson. It is instead a type of blade which Wilkinson had been producing to special order since the 1840s and which the Wilkinson records called the ‘flat solid’. This is similar in outline to the 1845 Wilkinson pattern blade, but with a totally different cross-section, having no fuller and being a shallow triangle or wedge-section. This gives better cutting performance, with edge geometry improved by the more narrow angle and consequently less friction passing through a target. It comes, arguably, at the expense of rigidity and durability.

2) The almost-straight blade is 1 1/4 inches wide, as opposed to the then-regulation 1 inch (1892 pattern), or the earlier 1845 infantry regulation of 1 1/8 inches (which after about 1870 it became increasingly popular to reduce to 1 inch with the 'Medium Infantry' option). The blade is also 33 inches long, which is very slightly longer than the usual 32.5 inches, though not at all as remarkable or unusual as the extra width.

3) The grip features the full-width tang construction devised by Charles Reeves at the beginning of the 1850s, first registered and then patented in 1853, and subsequently marketed by Wilkinson as the ‘Patent Solid Hilt’ (Wilkinson bought the rights to the patent and eventually bought Reeves’ entire business). This is also known and recorded in documents as simply the 'Patent Tang', or 'PT' for short in Wilkinson proof books.

The resulting sword, with its regulation 1827 pattern Rifles guard and 1895 pattern fully chequered backstrap and domed pommel, is a wonderful fighting weapon. It is, in my view, the culmination of many improvements made in British officers’ swords during the second half of the 19th century and conforms well with the sort of weapon that fencing authors like Captain Alfred Hutton and Captain Cyril Matthey would have approved of.

Whereas Colonel Fox had overseen the development of the almost purely thrusting blade of 1892 (as featured on the 1895 and 1897 pattern infantry officers’ swords), accompanied by Ferdinand Masiello’s Infantry Sword Exercise of 1895, Fox’s opponents Hutton and Matthey argued for a robust cut and thrust blade, together with a more rough and tumble style of fighting training, which foreshadowed some of the combative training methods of the Edwardian and WW1 era.

Fox and Hutton’s conflict would later culminate in their failed attempts at collaboration to design the next British cavalry sword. Fox eventually won, with his 1908 pattern design, but earlier prototypes show that Hutton had preferred to retain a compromise cut and thrust design.

Brodhurst's sword is a particularly big and beefy cut and thrust blade, with an extra strong hilt construction, which makes sense when we consider the identity of the officer and his regiment. The Ghurkhas were often on the frontline of keeping the Northern borders of the Empire secure and the officer himself was a product of India.

While the original scabbard or scabbards for this sword have been lost, it was probably originally equipped with a plated steel scabbard for parade and a wood-lined and leather-covered field service scabbard for wearing with a Sam Browne belt. The leather of both scabbard and belt should have been black for Rifles. Either scabbard would have looked quite wide, due to the proportions of the blade. There would also originally have been a black leather sword knot attached to the guard.

Major Bernard Maynard Lucas Brodhurst

Bernard Maynard Lucas Brodhurst was born on 6 August 1873 in Benares, Uttar Pradesh (India), the younger son of Mr. Justice Maynard Brodhurst of the Indian Civil Service and judge of the High Court, in the United Provinces of India, and Mrs. Mary Brodhurst.

He went to school at Clifton College and graduated as an Army officer through the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. He was in the cricket 11 at both these establishments and was also in the MCC. He played cricket for Hampshire on one occasion and was a right-handed bowler.

Brodhurst commissioned from Sandhurst in 1892 and was gazetted to the unattached list in September of that year. He was attached to the Border Regiment for a year in India and thereafter gazetted to the 4th Gurkha Rifles in September 1894, becoming a Lieutenant of that regiment in December 1894.

Waziristan 1894-95

Brodhurst first saw active service with the 4th Gurkha Rifles in the Waziristan Expedition of 1894-95, receiving the associated medal and clasp.

India General Service Medal with Waziristan clasp, courtesy of Spink:

https://www.spink.com/lot/18003000078

The Waziristan Campaign is not well known today, but happened on the North-West Frontier between India and Afghanistan. Tension had built in the independent state of Waziristan due to the establishing of fixed border lines with the neighboring states of India and Afghanistan (at British instigation). There were several rival tribal groups in the region, which also had varying interests and alliances, not to mention some strong religious fervor. Some groups sought a closer relationship with Britain, or Afghanistan, while others wanted to maintain independence.

The British and Indian Army were invited to establish a military camp at Wana in Waziristan, as there was an active petition by the Ahmadzai tribal group to become part of the British Empire. This camp was established, however other tribal groups, primarily religious elements of the Mahsud, were completely opposed to this.

The war erupted at 5.30am in the pitch black, on 3 November 1894, when around 2000 Mahsud tribesmen, led by a determined religious leader called Mullah Powindah, launched a surprise assault on the camp at Wana, which itself was manned by around 2500 soldiers.

The camp had not been fortified properly and no attack had been expected. British Army doctrine had not been properly followed and there was a price to pay. As a result, around 1000 of the attacking Mahsud penetrated the camp easily at first, their assault hitting the encampment of the 1st Gurkhas hardest.

In places the attackers engaged the unprepared defenders in close combat, bayonet and kukri against pulwar and charah. In other parts of the camp the Mahsud kept up a steady fire on the pinned-down defenders from longer range.

Gradually the 1st Gurkhas reformed and started bringing their firepower to bear on the attackers, with the rest of the camp finally deploying and coming to assist. With the artillery then coming into action also, the attackers retreated and the attack was over 30 minutes after it had started.

The 1st Punjab Cavalry (with 62 men) and Indian infantry sallied out from the camp to pursue the retreating enemy, the cavalry managing to cut down around 50 of them before they were fully dispersed into the countryside. The British Indian forces lost 23 soldiers killed, 43 soldiers wounded, with a further 43 camp staff killed and wounded in the attack on Wana camp.

This was a major blow to British and Indian Army reputation and prestige in the area. In response, a punitive Waziristan Field Force of around 8000 men was put together to out carry reprisals against Mahsud territories..

Part of this WFF was the Border Regiment, in which Brodhurst had initially served, though by the time of the campaign Brodhurst had already been gazetted to the 4th Gurkha Rifles, receiving his commission to Lieutenant around the time of the campaign. The 4th took part in the expedition alongside the 1st Gurkhas, who had taken the brunt of the attack at Wana.

For further detail about this campaign, I highly recommend reading here.

It seems quite likely that Brodhurst's experiences in Waziristan were the inspiration for his ordering of this new and special sword. Despite the commonly-held view by firearms enthusiasts, close combat was a feature of this sort of campaigning and in the descriptive accounts swords, lances and bayonets were clearly put to use. Given the attack on Wana and comparable events, it is quite easy to understand why a young officer would want the best set of weapons they could afford.

Events in Afghanistan were soon to prove that swords like this were a good investment, as in July 1897 (one month after the sword was purchased), the Malakand Uprising occurred.

The 4th Gurkha Rifles found themselves called to arms again, with the commencement of the Relief of Chitral in 1895 and the Tirah Campaign, also known as the Tirah Expedition, in 1897-98. Though I cannot find a record of Brodhurst having served on either of these campaigns. Nevertheless, this context of continuous small wars helps to put his service and his sword in the correct light.

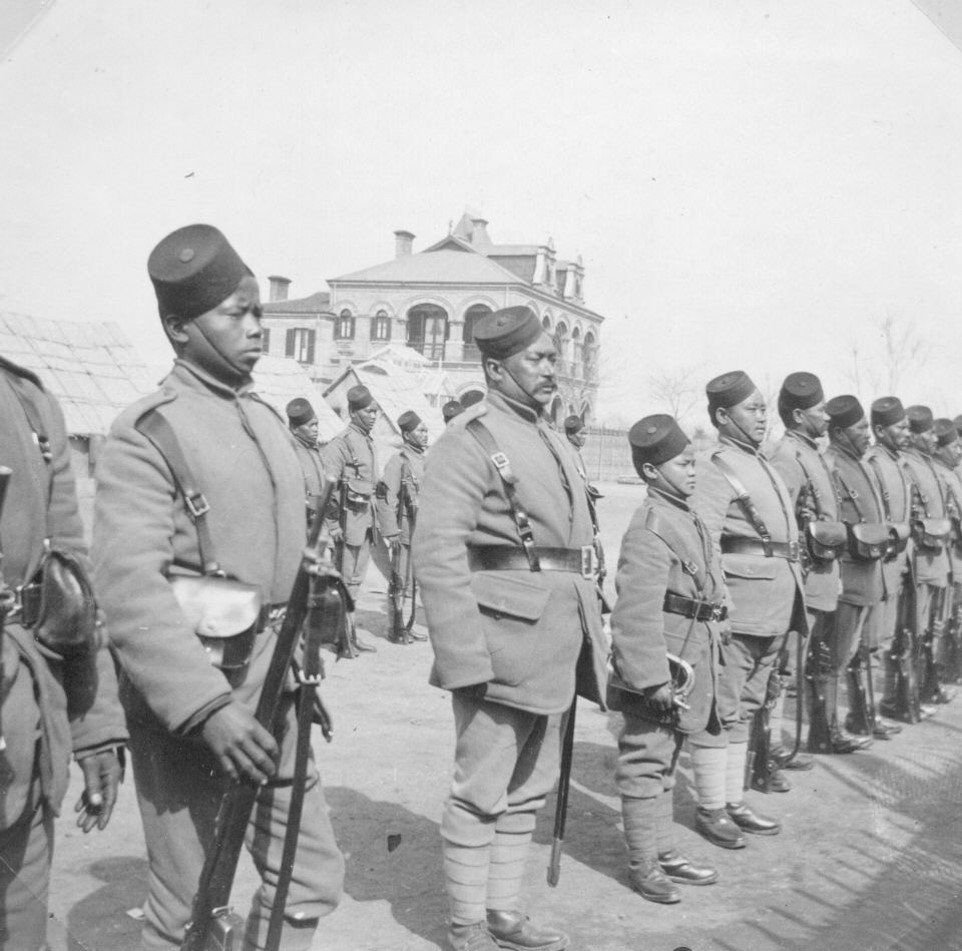

China 1900-01 - The 'Boxer Rebellion'

We know from Hart's Army Lists that Brodhurst received the medal for serving with the China Expeditionary Force (Boxer Rebellion) in 1900-1901.

Assuming Brodhurst did not serve on the Tirah Campaign with his regiment before this, then this would have been the first time his new sword was sharpened and taken on active service.

The Boxer Rebellion was named this after the uprising of Chinese nationalists who were opposed to foreign and Christian presence and interference in Chinese religion, politics and economics.

For decades, various European and Asian nations had been exploiting China's weak and internally fractured government, at the cost of China's populace. Gradually, assisted by agricultural stresses caused by colonialism, a feeling of anger and resentment had grown to critical mass, spurred on by fanatical martial arts practitioners (known often in Britain as Chinese Boxers).

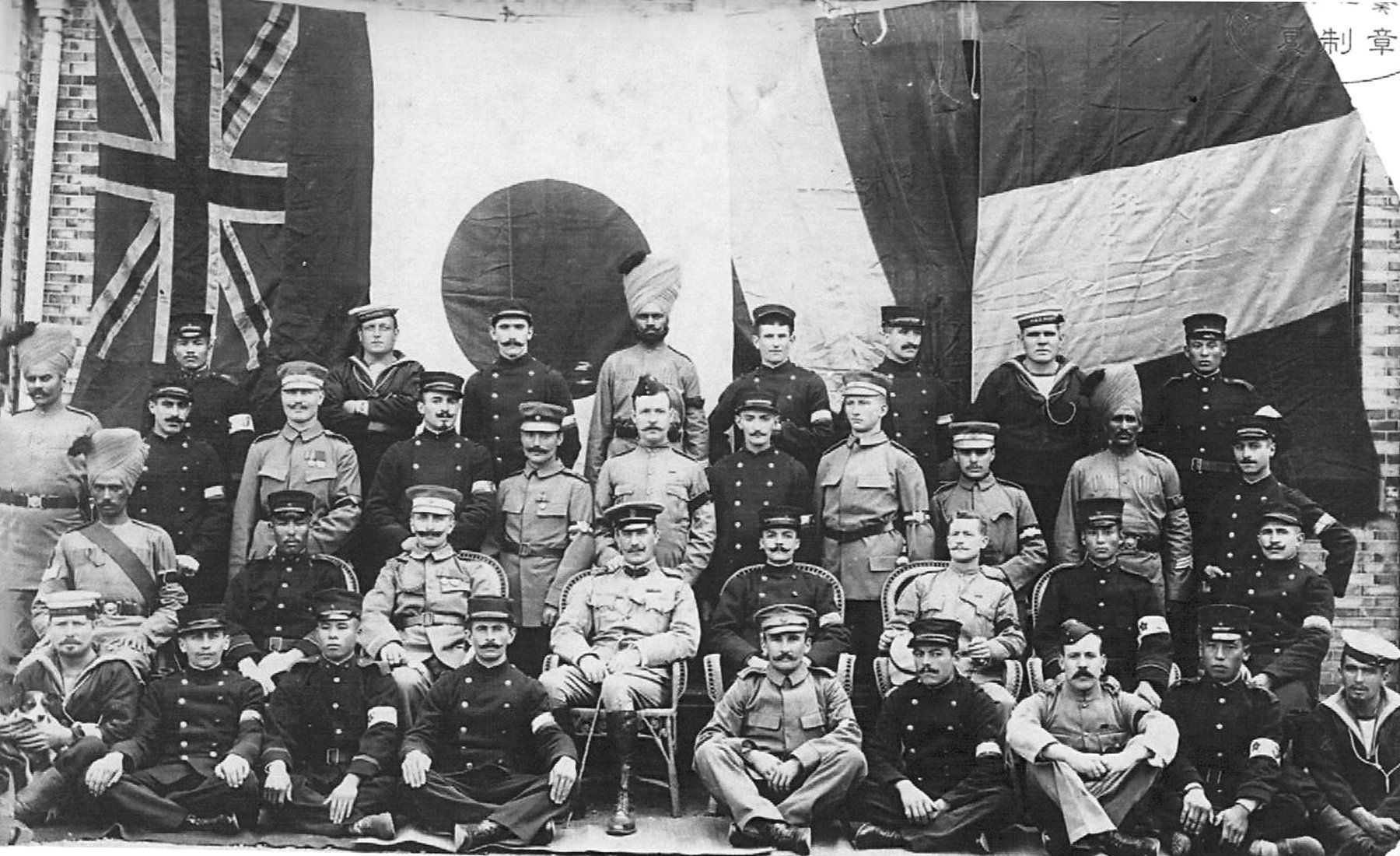

In 1897 and 98 incidents had occurred which had provoked German and other foreign powers to seek further control of Chinese territory and trade. When the Boxer uprising exploded in 1899 and the Europeans based in Peking (Beijing) were besieged, an unlikely collection of colonialist nations quickly jumped on the opportunity to extend their interests in China even further.

This collection of unlikely allies, all with similar and rival colonial aims, created an Eight Nation Alliance of American, Austro-Hungarian, British (and Indians), French, German, Italian, Japanese, and Russian forces. Among this Alliance was Brodhurst and the 4th Gurkha Rifles, following orders.

The Chinese Empress responded to the Alliance and invasion by throwing her support fully behind the Boxers, adding her Imperial Army to the cause. Though some other factions within China sided with the foreign Alliance or simply did their best to avoid getting involved.

The Imperial Army and Boxers were defeated after a series of actions on land and at sea, which I will not attempt to even summarize here. While it was a short war, it was a bloody and merciless one, with widespread slaughter and looting. I would encourage interested readers to read this chapter of history for themselves, as it is complex and fairly shameful on all powers involved. It also laid the foundations of 20th century politics in China and explains a lot of the modern World we live in now.

In any event, it is usually the job of soldiers to not ask why, but to do and die. The Boxer Rebellion in some ways was a culmination for 19th century colonialism and the cementing of the 20th century Superpowers. But it also foreshadowed some of the horror to come just over a decade later in WW1, when the powers of the Eight Nation Alliance would find themselves pitted against each other.

In 1900, Brodhurst was made Adjutant of his Battalion and was promoted to Captain in September 1901.

From 1903-06 he was the first Inspector of Signalling to the Imperial Service Troops. He was promoted to Major in September 1910.

World War One - The Great War

When WW1 was declared, Brodhurst was on leave in Chesterfield (where his brother M. S. Brodhurst lived and worked as a solicitor).

He immediately redeployed and traveled to Cairo in Egypt to meet up with his regiment, the 4th Gurkha Rifles, who had traveled there from India to fight the Ottoman Turkish Army.

Brodhurst was stationed with the various other regiments of Gurkha Rifles for some time at the Suez Canal, which was a critical tactical objective during WW1 for Britain to maintain contact and supply with India. It was later to come under large scale attack by German and Turkish forces and in preparation for that, Brodhurst and his men were involved in supervising the digging of trenches and other fortifications along the Canal.

However, the regiment was soon ordered to the Western Front, as part of Indian Expeditionary Force A, arriving in Marseillies on 30 November 1914.

The Battle of Givenchy

The first major engagement on the Western Front that we have Brodhurst recorded as taking part in was the Battle of Givenchy.

He is recorded as being seriously ill, but demanding and being allowed to take part in the attack anyway. This began on 19 December 1914 at 3.10am, in freezing rain between La Bombe Crossroads, near Neuve-Chapelle, and La Bassée Canal.

The Lahore Division set out from the village of Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée and took the first two German lines, while coming under heavy machine gun fire. The Garhwal Brigade and the Gurkhas captured 300 metres of enemy lines at Festubert.

The enemy regrouped and countered quickly, making extensive use of hand grenades and with heavy artillery support bombarding the Indian troops. The Germans also succeeded in detonating mines under the British and Indian lines. German infantry advanced on Festubert, surrounded Givenchy and captured over 800 British troops in the process.

British and Indian losses in this engagement were very high, with the British/Indian force losing around 4000 men compared to the German Army’s 2000. The weather conditions contributed to a lot of casualties, with many troops suffering trench foot and frostbite. The Indian troops were particularly hard hit by both the weather and the German Army.

On Christmas Day 1914 Brodhurst is recorded as returning to England for treatment of frostbitten feet, a stark reminder of the grim conditions that soldiers were facing. Brodhurst remained in London, being treated in a private nursing home, until in March 1915 he returned to active duty on the Western Front.

The Battle of Neuve Chapelle

Various sources record that Major Brodhurst fought with the 4th Gurkha Rifles at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle between 10-13 March 1915, as part of the Sirhind Brigade.

During this battle, British and Commonwealth, particularly Indian, troops managed to smash through German lines, taking ground and prisoners. This was partly achieved thanks to the efforts of the Royal Flying Corps, who had for weeks previously gained air superiority over the area and this in turn led to greater mapping and recconnaisance of the front.

However, the attack was not exploited effectively and casualties were high. It proved to be a useful lesson for future operations at least, though it has been noted that the heavy artillery barrage that the Germans came under from British forces in particular, led them to create more effective fortifications soon after as a result.

The Second Battle of Ypres

At the Second Battle of Ypres, where my own great-grandfather as a Colonel of the RAMC suffered poisoned gas, Major Brodhurst found himself commanding the 4th Gurkhas and second in command of the Sirhind Brigade.

The Second Battle of Ypres involved a series of engagements from 22 April to 25 May 1915, as both sides vied for control of this strategic Belgian town.

I will defer at this point to the text from the excellent book The Indian Corps in France, by Lieutenant Colonel John Walter Beresford Merewether and Frederick Edwin Smith, Earl of Birkenhead, recounting the events of 27 April 1915:

“The Sirhind Brigade advanced on a two-battalion front, the 1/4th Gurkhas under Major Brodhurst on the right, and the 1/1st Gurkhas commanded by Lt-Colonel W. C. Anderson on the left, with the 4th Liverpools and the remainder of the 1st Highland Light Infantry and the 15th Sikhs in support.

In passing the ridge, the attack came under severe frontal cross fire from rifles and machine guns, as well as from several other directions. The enemy had registered the range of every likely spot with great accuracy; hedges and ditches which would give any sort of cover had all been marked down, and casualties were heaviest in their vicinity.

Major Brodhurst, commanding the 1/4th Gurkhas, was killed early in the attack, the Adjutant, Captain Hartwell, being wounded by his side at the same moment.

Three British officers and about thirty men succeeded in reaching a large farm at the bottom of the slope, which had apparently been used as a Canadian R.E. [Royal Engineers] depot. Here they held under a shattering fire, but the remainder of the battalion could not join them until about 4 p.m., when Lt-Colonel Allen, commanding the 4th King’s, seeing that the 1/4th Gurkhas were held up, determined to reinforce.”

Thus tragically, like so many men of his generation, ended the career and life of Major Brodhurst, aged 41.

He is buried at La Brique Military Cemetary No. 2 (Plot I, Row G, Grave 21) in West-Vlaanderen, Belgium.

Posthumously, M. S. Brodhurst, claimed the War Medal and Victory Medal, which his brother Bernard had earned through his service:

Conclusion

Researching this sword and the officer who ordered it reminds us that only 100 years ago people were fighting and dying with these things that we collect.

Whatever our modern view of the politics of those times, these were people who believed in duty and their cause, and they committed their lives to that belief. Their bravery to me is awe-inspiring and moving. The graphic period accounts are far from the modern Hollywood view of war and serve as a reminder of how lucky we are, who live in peace.

While most areas under Western-control saw mechanized and long-range warfare by 1897, the areas where the Gurkha Rifles were campaigning and policing in India and the North-West Frontier still saw close combat at this time, where the kukri and sword were still important weapons of attack and defence. This is the historical context in which this sword sits, if not really in the poison gas, machine gun bullet and shrapnel-laden air of Ypres.

This sword is an extraordinary piece for an extraordinary man, who presumable expected to need a reliable and effective sidearm in Waziristan, Afghanistan, India or China. Brodhurst obviously had strong views about sword design and committed those to manufacture.

It seems fitting to me that such a sword belonged to an officer born in India, who served in India and who fought and died alongside Indian and Nepalese comrades, who sadly have not received the same recognition that their European comrades have in subsequent years.

The Gurkhas are rightly famous and their fighting spirit now near legendary. They still serve in both British and Indian Armies around the World. Major Brodhurst of the Gurkha Rifles died aged 41 without wife or children, alongside his Nepalese, Indian and British Commonwealth comrades, but he will be remembered.